By 1910, fewer than 45,000 Black people lived in Chicago. By 1970, that number had jumped to over 800,000. This wasn’t just a change in population-it was a complete reshaping of the city’s soul. The Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of Black families from the rural South to Chicago, fleeing violence, poverty, and Jim Crow laws. What they found wasn’t perfect, but it was freedom. And they built something extraordinary with it.

Why Chicago?

Chicago didn’t just happen to be a destination-it was actively recruited. Northern factories needed workers. The railroads, stockyards, and steel mills were desperate for labor. Companies sent agents down South with promises of steady pay, better housing, and dignity. Postcards and letters from relatives painted a picture: jobs that paid real wages, schools that didn’t turn kids away, and the chance to vote without fear.

For many, Chicago meant escape. In Mississippi, a Black man could be lynched for looking a white woman in the eye. In Alabama, sharecroppers were trapped in debt that lasted generations. Chicago offered something even more powerful than safety: possibility. By 1917, over 50,000 Black Southerners had moved to the city. By 1920, it had the largest Black population outside the South.

The South Side Becomes a Hub

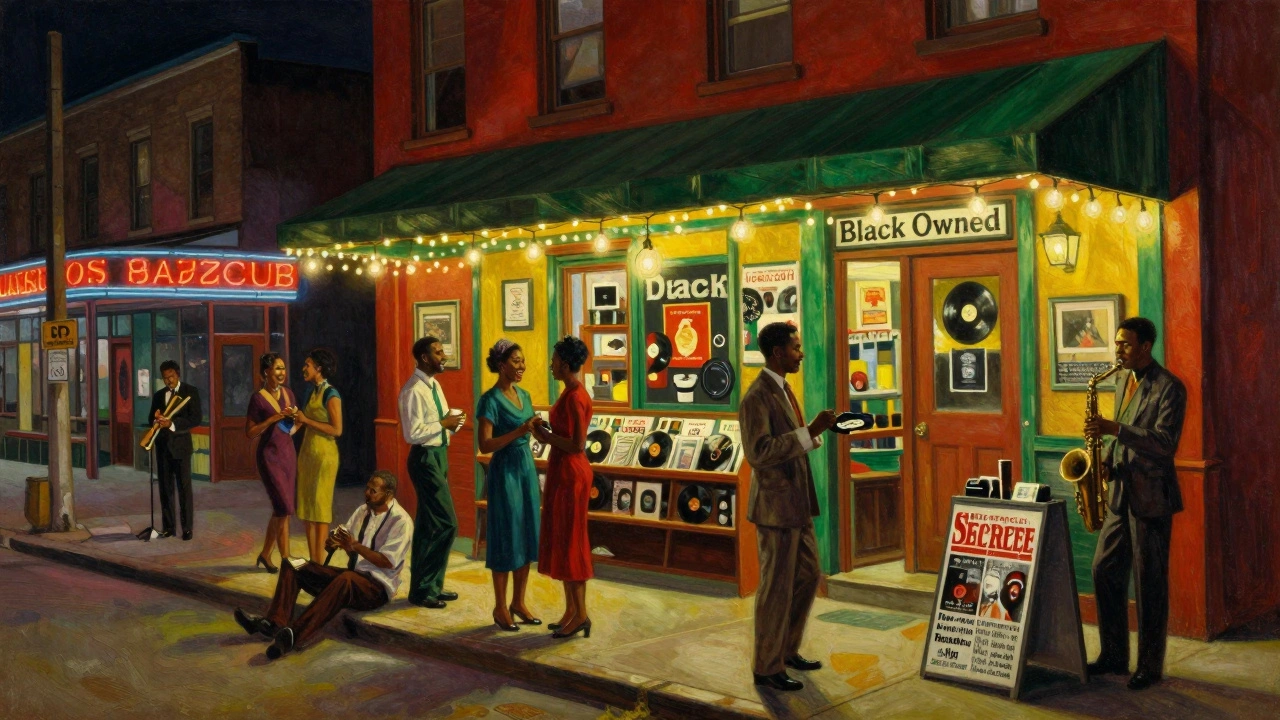

The Black community didn’t spread evenly. It clustered-first along the South Side, between 18th and 51st Streets, and later expanding into neighborhoods like Bronzeville. These weren’t just neighborhoods; they became cultural engines. Black-owned businesses lined State Street: barbershops, funeral homes, restaurants, newspapers, and record stores. The Chicago Defender is a nationally circulated Black newspaper founded in 1905 that played a crucial role in encouraging migration by exposing Southern injustices and highlighting job opportunities in the North. Its editor, Robert S. Abbott, didn’t just report news-he mobilized people.

By the 1930s, Bronzeville had more Black-owned businesses than any other urban area in the country. There were over 100 Black-owned banks and insurance companies. The Dreamland Ballroom hosted Duke Ellington. The Regal Theater drew crowds from across the city. You could buy a suit from a Black tailor, get your hair done by a Black stylist, and hear live jazz from a Black band-all without stepping into a white-owned space.

Culture That Changed America

Chicago didn’t just absorb Southern culture-it reinvented it. The blues, born in Mississippi, got louder, faster, and more electric in Chicago. Muddy Waters turned his acoustic guitar into a roar. Howlin’ Wolf’s voice shook the walls of small clubs on Maxwell Street. These weren’t just songs-they were stories of loss, survival, and pride. The music didn’t stay in the South Side. It traveled north to Detroit, to New York, and eventually to London and beyond.

Writers like Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks emerged from Chicago’s Black neighborhoods. Wright’s Native Son shocked the nation with its raw portrayal of Black life under pressure. Brooks became the first Black person to win a Pulitzer Prize in poetry. Their work didn’t just reflect Chicago-it defined it.

Even sports changed. The Negro Leagues found a home in Chicago. The Chicago American Giants drew crowds larger than some MLB teams. And when Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, it was Black Chicagoans who cheered loudest-not just because he was a player, but because he represented everything they’d fought for.

Hardships Behind the Progress

But freedom didn’t mean equality. Redlining locked Black families into overcrowded neighborhoods. Landlords charged higher rents for worse apartments. Schools were underfunded. Police didn’t protect Black neighborhoods-they patrolled them like occupied territory.

The 1919 race riot killed 38 people and left hundreds injured. It started over a single incident-a Black teenager swimming too far into a segregated beach-but it exploded into a citywide firestorm. Homes were burned. Businesses destroyed. The city never fully made amends.

By the 1950s, public housing projects like Cabrini-Green were built to house the growing population. But they became symbols of neglect. Broken elevators, rats, and poor maintenance turned them into prisons instead of homes. Still, people stayed. They organized. They fought. They built churches, community centers, and mutual aid networks that kept families alive.

The Legacy Lives On

Today, you can still feel the echoes of the Great Migration in Chicago. The food-chicken and waffles, smothered pork chops, sweet potato pie-still comes from Southern roots. The jazz clubs on the South Side still play late into the night. The annual Black Metropolis Convention draws thousands to honor the history of Bronzeville. And the city’s political power? It’s rooted in the voting blocs that Black migrants built.

Chicago’s Black community didn’t just adapt to the North-they changed it. They created institutions, shaped music, influenced literature, and forced the city to reckon with its own contradictions. The Great Migration wasn’t about leaving the South. It was about claiming a future.

What triggered the Great Migration to Chicago?

The Great Migration was driven by a mix of push and pull factors. In the South, Black people faced lynching, Jim Crow laws, and exploitative sharecropping systems. At the same time, Northern industries like Chicago’s stockyards and railroads needed workers due to World War I and a drop in European immigration. Factory owners sent recruiters down South, offering steady wages and better living conditions. Newspapers like the Chicago Defender spread the word, publishing letters from migrants and job listings that made Chicago seem like a land of opportunity.

How did the Black population in Chicago change during the Great Migration?

In 1910, Chicago had fewer than 45,000 Black residents. By 1920, that number had doubled to over 100,000. The biggest surge came between 1916 and 1919, when over 50,000 people moved north in just three years. By 1940, the population reached 278,000. After World War II, another wave brought the total to over 800,000 by 1970. This made Chicago home to the largest Black urban population outside the Deep South.

What role did the Chicago Defender play in the migration?

The Chicago Defender, founded by Robert S. Abbott in 1905, was more than a newspaper-it was a movement. It exposed Southern lynchings and racial violence, while also publishing job openings, train schedules, and letters from migrants who had already moved north. The paper was distributed across the South via Pullman porters, who slipped copies into suitcases and carried them into rural towns. Its bold headlines like “Great Migration Begins” and “Chicago Is Calling” convinced countless families to leave everything behind. Historians credit the Defender with influencing up to half of all Black migration to Northern cities.

How did Black Chicagoans build community despite discrimination?

Faced with redlining, housing discrimination, and police neglect, Black Chicagoans created self-sustaining networks. They opened businesses, churches, and mutual aid societies. The South Side became a hub of Black entrepreneurship-with over 100 Black-owned banks, insurance companies, and newspapers. Churches like Olivet Baptist became centers of political organizing and social support. Women’s clubs provided childcare and job training. Even in the face of segregation, they built institutions that gave people dignity, safety, and a sense of belonging.

Why is Bronzeville considered the heart of Black Chicago?

Bronzeville, centered around 35th Street and State Street, became the cultural and economic epicenter of Black Chicago during the early 20th century. It was home to the Regal Theater, the Dreamland Ballroom, and the first Black-owned radio station. Writers like Gwendolyn Brooks and Richard Wright lived here. Musicians like Louis Armstrong and Muddy Waters performed in its clubs. At its peak, it had more Black-owned businesses than any other urban area in the U.S. Even after urban renewal projects and economic decline, Bronzeville remains a symbol of resilience and cultural pride.

What’s Left Today?

Chicago’s Black population has shrunk since its peak in the 1950s, but the legacy hasn’t faded. The music still echoes in the blues clubs of the South Side. The churches still hold voter registration drives. The schools still teach kids about the Great Migration-not as a footnote, but as a turning point in American history.

When you walk down 47th Street today, you’ll still find the same soul food joints, barbershops, and record stores that opened in the 1920s. They’ve been passed down through families. They’ve survived riots, economic crashes, and neglect. And they’re still here-not because they were lucky, but because they were fought for.

The Great Migration didn’t just change Chicago. It changed the nation. And its story isn’t over-it’s still being written, one block, one song, one vote at a time.